My last article ‘I ran a Marathon on a Coffee Bean’ sparked quite a lot of interest. My approach is not exactly conventional and the article was absent of many key concepts in traditional sports nutrition namely carb loading, gels and that magic number of ‘grams per hour.’ In fact, if we have a closer look at the current conventional recommendations listed here, my suggested daily carbohydrate intake is 360g per day. I was interested to see what these recommendations would actually equate to on a plate. Firstly, I established that in order to meet these kinds of numbers, I would have to include what I refer to as ‘dirty carbohydrates’ from cereals, highly refined grains, low fat dairy, sugary yoghurts and the dreaded sports drinks.

This is what it could look like:

Breakfast: 1 and a half serves of Nutri Grain (40.5g) with 1 and a half cups of low fat milk (20g). Total carbs=60.5 grams

Snack: Smoothie consisting of 1 and a half bananas (34g) plus a cup of low fat milk (12g) plus a tub of low fat yoghurt (25g) and some protein powder. Total carbs =71 grams

Lunch: 1 sandwich with 2 slices of bread (35g) plus an orange (12g). Total = 47g

Afternoon snack: 4 x Rice cakes (30g) with nut butter. Total carbs = 30g

Post training drink: Gatorade (30g). Total carbs = 30g

Dinner: ½ a cup of cooked rice (30g) with 2 potatoes (34g) plus meat and other vegetables (negligible). Total carbs = 64g

Supper: Milo 1 serving (12g) with 1 cup of milk (12g). Total carbs = 24g

Daily total of carbs = 326.5 grams (please note that this is for example purposes only and the numbers listed are averages of major brands).

I still haven’t quite hit my daily quota but I am sure you get the idea. I’m honestly convinced that if I followed these kinds of recommendations for just a few short weeks, my fairly consistent 60kg would soon be approaching 70kg and so on. Not to mention the belly bloat from this much wheat and gluten. In addition to daily carbohydrate recommendations, traditional sports nutrition indicates that during an endurance event, I may require up to 90g of carbohydrates per hour. So hang on, whilst I’m out there, pumping blood around my body in order for my legs and arms to carry me to the finish as fast as possible, I am supposed to EAT?

I find this advice difficult to swallow… pardon the pun. Here are just 3 major reasons why I don’t agree with these recommendations:

- Firstly: In order to come anywhere close to the recommended daily carbohydrate intake, you must include a lot of highly refined carbohydrates from heavily processed foods. These sources tend to be high in gluten, additives, preservatives, artificial flavours, colours, sugar and unfermented processed soy. Every single one of these ingredients is inflammatory to the body, damaging to the gut lining and may inhibit the immune system. Furthermore, I really can’t imagine having much room leftover for essential fats and proteins if I am required to ingest this many carbohydrates.

- Secondly: When carbohydrates are the primary component of every meal, blood sugar and insulin levels rise and fall like a rollercoaster ride. The constant need for these insulin surges; meal after meal, day after day, year after year; may lead to insulin resistance down the track. This is the pathway to other far more serious conditions including metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes and obesity. Yes, even athletes develop these conditions.

- Finally: when we exercise, our heart works harder to pump blood to the extremities of the body, including the muscles which require nutrients and oxygen in greater amounts. The blood vessels to these outer extremities actually dilate whilst the vessels around the stomach and kidney become narrower. This makes the whole process of digestion extremely difficult. Last time you had an energy gel or a snack during an event…. How did it go down? Did it hesitate half way? Feel like it might come back up again? Is it any wonder?

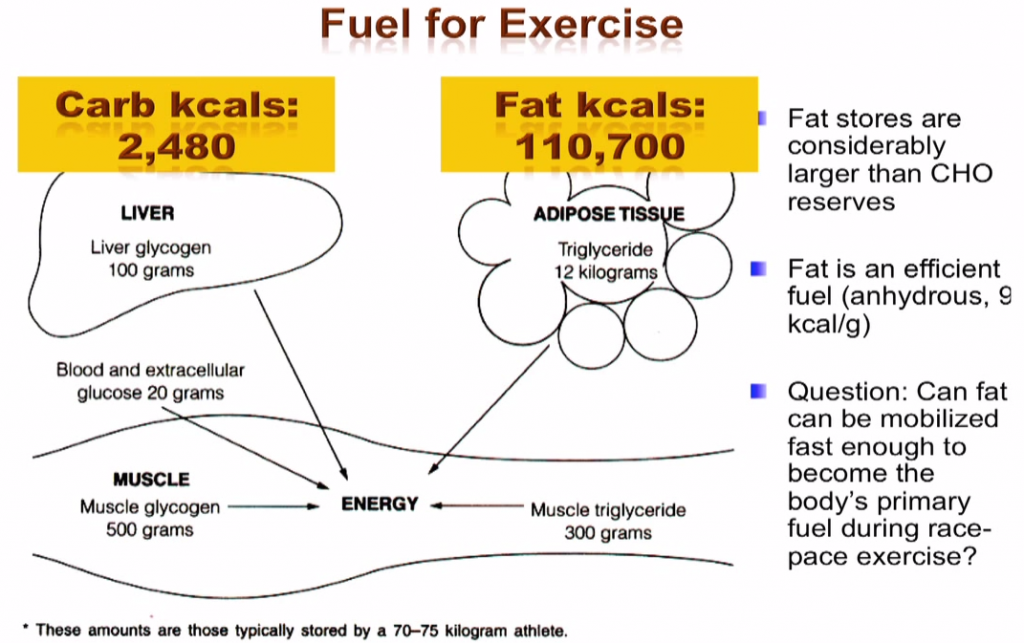

Well, traditional sports dietetics is built on the premise that we use glucose (sugar) as energy. Specifically, we use up the glucose that is stored as glycogen in the muscles and liver during endurance events. There is approximately 2500 calories worth of energy stored in the form of glycogen within our bodies and this is our ‘gas tank’ if you like during sporting events. The whole premise of ingesting carbohydrate as you move is to prevent the tank from running out of gas, otherwise known as bonking. But 2500 calories isn’t going to get you that far. Whilst we all burn calories at slightly different rates, a 70kg man running at 10km / hour will use up approximately 800 calories per hour. Do the math and this means that he’s got just over 3 hours of fuel in the tank…. Or 30km. Ever seen someone hit the wall in a marathon at 30km? I bet you have…. it’s an all too familiar state of affairs. And unless you have an iron gut chances are you aren’t going to keep up with your own refuelling requirements so there’s a high chance you’re going to bonkville too.

Good news – there’s an alternative. See, what we have been ignoring for such a very long time is that in addition to those 2500 calories of stored glycogen, we have another pretty nifty tool in (or around if you like!) our belt – literally –I am referring to stored body fat. And seriously, who is going to say no to burning off a bit of body fat during an endurance event? Not me. The cool thing is that even a lean athlete will have at least 100,000 calories worth of energy available within stored fat sources and we are able to train our bodies to tap into these reserves. It’s that simple! Yes… THIS is what all the fuss is about!

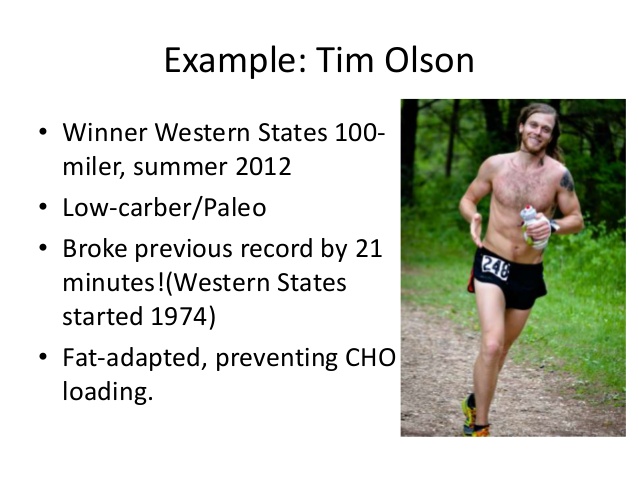

Contrary to what critics may say, fat adaptation for athletes does not necessarily severely restrict carbohydrate intake. For some, nutritional ketosis may be worthwhile considering (more on that later, but this needs to be under the guidance of a qualified health practitioner), but for most people, fat adaptation is about retraining the body so that it becomes more metabolically efficient. In order to explain this effectively, let’s consider the Respiratory Quotient; a method of testing how much energy is coming from carbohydrates and how much is coming from fat, during an exercise session. An athlete with an RQ of 1.0 is solely relying on carbohydrates during exercise, whilst an athlete with an RQ of 0.7 is burning fat exclusively. Obviously intensity of output does play a part here, but can you see the benefits of sitting closer to the 0.7 score as opposed to 1.0 on this scale? An athlete who is able to tap into some of his or her existing fat stores is going to be capable of a higher output for a longer amount of time with less fuel. This is a win / win in my book. Achieving optimal metabolic efficiency for your own sport and your own individual body may make you ‘bonk proof’ and means that your nutrition is no longer left to chance.

In addition, fat adapted athletes tend to experience advantageous body composition changes and may experience better recovery as a real food diet has superior nutrient density. The information in this article is just the beginning and serves as an introduction to fat adaption or metabolic efficiency for athletes. This is not a blanket approach to nutrition, it is simply a template. Just to reiterate, the absolute foundation of this approach is real food, as unrefined as possible. Once you switch to a real food diet, your carbohydrate intake will automatically lower and your fat intake will increase because this is how real food is designed… for a reason. Beyond that, there are many other concepts for you to consider such as the ‘train low, race high’ approach, nutritional ketosis, electrolytes and fluids and fasted training for adaptation. Start your research and see what you find. There is nothing scary about this approach to sports nutrition… unless you think throwing out the Nutri Grain and Ski D’Lite sugar laden yoghurt is a bad thing. Have you seen what I eat on my Instagram account? I’d take that food over processed, packaged stuff any day of the week.

This article is a thought provoker – I am prodding your mind and asking you to consider another way. If you want some more assistance you can Work with Me here. I can show you how simple real food living truly is.

Good luck on your quest for life long athletic longevity and your journey to bonk proof :).